Every year, around 250,000 people in the United States are victimized by hate crimes—crimes based in bigotry and biases that terrorize people because of who they are or what they believe.1 Not only are these crimes usually targeted at minority groups, but they also rip apart the unity of our communities.

With so much destruction left in their wake, what motivates someone to engage in this type of hate-filled violence? The reasons are complex and multi-faceted. Here’s a closer look at hate crimes in the United States as well as the psychology behind them.

What Is a Hate Crime?

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), a hate crime is a violent crime intended to harm or intimidate people or damage their property because of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, disability, religion, or other minority group status.2

Sometimes referred to as bias crimes, hate crimes are perpetrated by people who believe they are justified in acting out violently.

Some scholars believe the term “hate crime” is outdated and inaccurate because what causes people to act is rarely limited to hate alone. Instead, it’s a lethal mix of emotions ranging from from anger and fear to animosity and indignation. In fact, according to the FBI, hate alone is not a crime but instead an added component of offenses like murder, arson, vandalism, and assault.2

It’s also important to note that not all violence motivated by hate will be charged with a hate crime. For instance, according to the Anti-Defamation League, higher-level felonies like murder already have serious consequences, and the perpetrator is often not charged with a penalty involving a “lesser” sentencing.3

Why People Commit Hate Crimes

According to the American Psychological Association, “hate crimes are an extreme form of prejudice that is made more likely in the context of political and social change.”4

For instance, political bullying and discourse can lead people to devalue others that they know very little about, especially if they feel like their livelihood or way of life is being threatened (even when this is unsubstantiated by reality).

Likewise, they note that offenders aren’t necessarily motivated by hate, but instead may be fearful or angry instead. Ultimately, these feelings can lead them to dehumanize unfamiliar groups of people and target them with aggression.4

Additionally, people tend to view groups of people that they’re not a part of as more homogeneous than their own group. In other words, when they see someone from a minority group, they are less likely to see them as an individual and more likely to apply biases.

They assume they know what the person is like and never really see them apart from the group. Consequently, these assumptions along with prejudices and stereotypes can become the foundations for hate crimes.

Motivating Factors of Hate Crimes

When it comes to understanding the psychology behind hate crimes, law enforcement agencies like the FBI often cite a study conducted by sociologists Jack McDevitt and Jack Levin.

In their study, McDevitt and Levin identified four primary motivations of people who commit hate crimes. These motivating factors include thrill-seeking, defensive, retaliating, and mission-oriented behaviors.5 Here is a closer look at each motivating factor.

Thrill-Seeking Offenders

Driven by an imbalanced need for excitement and drama, these offenders are often people seeking to stir up trouble. Many times, there is no real reason for their crimes. They are simply interested in the rush of excitement they get from wreaking havoc on the lives on others, especially those who can’t defend themselves.

For this reason, they gravitate toward people who are more vulnerable because of their race, sexual identity, gender, or religious background. They also typically believe that society doesn’t care what happens to these victims. They may even believe others will applaud their attacks.

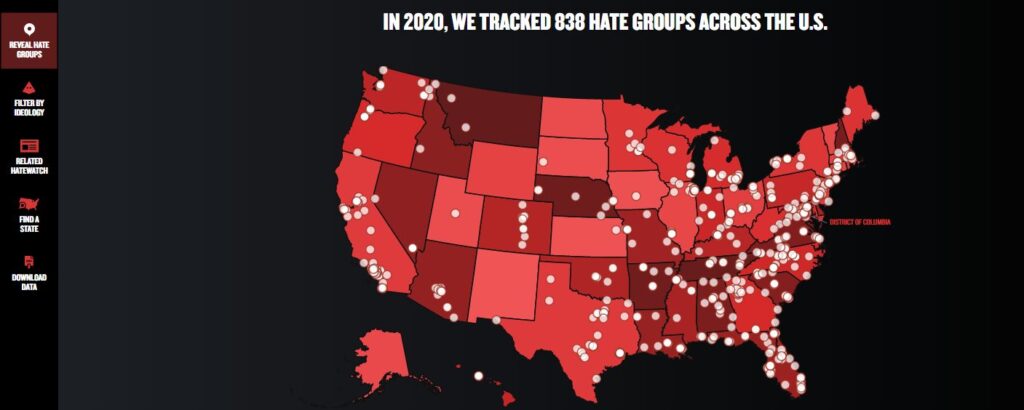

When it comes to thrill-seeking offenders, they are responsible for 66% of the hate crimes in the United States according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).6 What’s more, in 90% of cases, those who commit these types of crimes don’t even know their victims.

Defensive Offenders

When it comes to defensive offenders, these attackers see themselves as defending something important to them—like their communities, their workplaces, their religion, or their country. Unlike the thrill-seekers who attack their victims by chance and without warning, defensive offenders target and victimize specific people.

Defenders also rationalize and justify their actions as necessary steps in order to provide protection and keep threats from materializing. And, just like thrill-seekers, they show little or no remorse for their actions.

Instead, they feel justified. They also believe that most of society supports what they do but are just too afraid to act.

Overall, defensive offenders are responsible for 25% of the hate crimes in the U.S. They rationalize their attacks by identifying some sort of threat to themselves, their identities, or their communities.6

A former New Jersey police chief, Frank Nucera Jr., is an example of a defensive offender who injured a Black teenager while in police custody. He shouted a racist claim that Black people were part of ISIS and that Donald Trump was the last hope for whites.

Retaliatory Offenders

Motivated by revenge, these offenders are often motivated by something that happened in their lives. Either they were victimized personally or they witnessed an incident involving hate or terrorism and that has been the catalyst for their crime.

Additionally, they often act alone and target those affiliated in some way to the original offenders. For instance, the retaliatory offender’s target may be of the same race or religion as those they blame for something else, but who had nothing to do with the original crime.

With retaliatory attacks, offenders are acting out in response to a real or perceived crime committed against themselves or others.6 These attacks comprise 8% of the hate crimes committed each year.

An example of retaliatory offenders could be seen after the 9/11 attacks. Hate crimes against Arabs and Muslims rose exponentially following 9/11.

Mission Offenders

While this type of hate crime is rare — representing only 1% of the hate crimes committed — it is often the most hate-filled and violent. These offenders make a career out their hate and often write at length about their feelings. They also usually have elaborate, premeditated plans of attack.6

The people who commit these crimes are often connected to groups that share their views and see themselves as crusaders for a race, religion, or political cause. Their goal is to wage war against their perceived enemies.

Overall, mission offenders write lengthy manifestos, visit hate websites that support their views, and are willing to travel in order to target people at specific sites or locations. Because these offenders believe that the system is rigged against them, they feel justified in attacking innocent people.

Additionally, their crimes often look a great deal like terrorism. Consequently, scholars often believe that the two extremes often overlap. For instance, white supremacist Dylan Roof who killed nine people in a predominately Black church in Charleston and Omar Mateen who killed 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando would both be considered mission offenders.

A Word From Verywell

Unfortunately, hate is prevalent in the United States. But it doesn’t have to be that way. You can help put an end to hate crimes, by speaking out against biases, prejudices, and stereotypes. After all, understanding and appreciating one another as individuals — rather than dehumanizing people — is the first step toward ending hate in this country.