ew issues in American life have been as intransigent as race. In every century, race has presented the nation its greatest paradoxes, challenges, and opportunities, calling into question time and again the principle of equality on which it was founded.

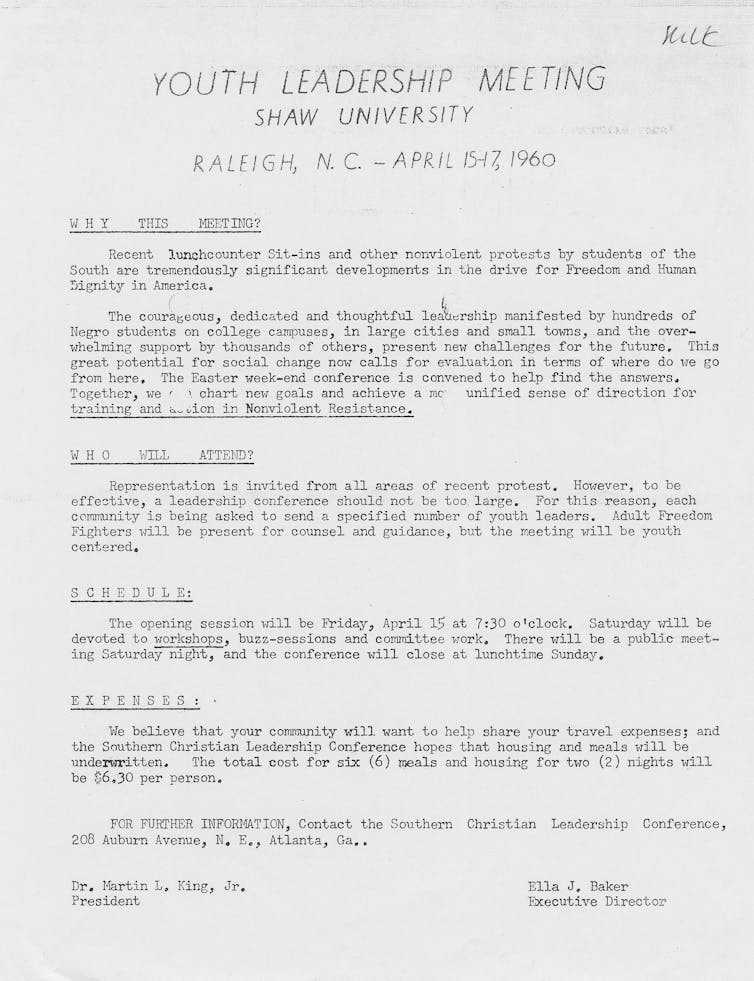

During the 1950s and 1960s, the golden era of civil rights activism, the civil rights movement mobilized the nation’s collective consciousness around issues of racial equity. The U.S. Supreme Court officially ended legal school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas in 1954. Congress passed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Black political participation increased dramatically. In 1964, only 5 blacks served in the U.S. Congress. By 1998, the number had grown to 39.

But the victories of the movement, however decisive they seemed at the time, did not bring the long-term parity that activists and policymakers hoped for. Bread-and-butter issues such as unemployment, substandard housing, inferior education, unsafe streets, escalating child poverty, and homelessness supplanted the right to vote, eat at a lunch counter, and attend desegregated schools. As new issues arose, appearing and intensifying in ways that fell beyond the scope of the legislation and social reforms, the old civil rights model—one that relied mostly on judicial and protest remedies—seemed less and less effective in dealing with them.

Contributions of the Movement

The civil rights movement made lasting contributions to the nation. Above all, it helped eliminate the legal apartheid that had dogged the United States since its earliest days. It also created a national expectation that individuals and groups had the right to petition their government to right legal wrongs affecting them. In its wake there developed a broad base of constituent interest groups—women, the elderly, children’s rights advocates, the handicapped, homosexuals, environmentalists—that emphasize the rights of affected parties to be a critical part of the decisions affecting their interests.

Ironically, the emergence of those constituent groups, each with its own divergent interests, made it much more difficult to sustain the old civil rights coalition of members of labor, the faith communities, and sympathetic whites and blacks to advance the new issues of post-civil rights America. Indeed, the dominant ethos of the sixties, racial integration and equality, has given way to an implicit but insidious assumption by many whites and blacks today that voluntary racial isolation and segregation are acceptable even among those whose fundamental interests are similar.

The American citizenry is also divided over whether the unfinished civil rights agenda has its origins in race or social class, and even whether government reforms such as affirmative action should address the lingering problems. The compelling evidence of African-American progress found in the burgeoning middle class helps explain why opponents of a race-based agenda feel the way they do. Meanwhile poverty in a large and intractable black underclass reaches deep into inner cities and rural communities nationwide and decisively constricts the life chances for affected parties, particularly children.

The Unfinished Civil Rights Agenda

Two issues remain on the civil rights agenda. The first is addressing the persistence of racial disparities. The second is redefining the agenda to fit a vastly changing American demographic profile.

Black-white inequality persists in income, education, health, housing, technology access, and safe communities. The national media increasingly report on racial profiling in what has come to be euphemistically referred to as “driving while black,” in the denial of equal access to rent or purchase housing, and in disparities in arrests and sentencing in the criminal justice system.

Many still view government intervention as the most effective means to provide the leadership to eliminate the disparities. But others argue that the responsibility for solving these problems rests neither entirely with government, nor with the voluntary, private, sector, but with a coalition of government, civil society, business, and individual initiatives. They see an invigorated role for faith-based groups, particularly those serving African Americans, and also a stronger role for industry in hiring and training the most indigent and least prepared.

The second issue on the civil rights agenda involves the rapid growth in the immigrant population since 1965. Individuals of Hispanic origin now outnumber African Americans. By 2050, the majority-minority population paradigm on which race and ethnic relations have traditionally rested in this society may be a thing of the past. As a nation, we have already moved away from the traditional white-black model of race relations to one that reflects the nation’s broad diversity—in race, ethnicity, gender, and lifestyle.

The increase in interracial and interethnic marriages is already changing the historical perceptions of what it is to be a member of the “white” or “black” race. High-profile individuals like golf professional Tiger Woods represent a generation of Americans who are redefining race by embracing their ethnic and racial diversity and its broader societal implications.

It is conceivable that at mid-century, Americans will view race in fluid rather than fixed and precise terms, not unlike the way Brazilians see their multiracial population.

The Need for New Models

One of the shortcomings of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s was its failure to envision the need for a fluid model of action to address new civil rights issues in the years ahead. And still the search goes on. Indeed, the issue today is how to develop flexible remedies to black-white disparity, the nation’s changing racial and ethnic diversity, and white poverty. One way is to rebuild the black voluntary sector that was for a time supplanted by the black electorate. Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition was a step in the direction of pitching a huge tent under whose shelter new and old minorities and the poor could find common issues and agendas. Martin Luther King’s proposed Poor People’s campaign in 1967 also recognized that a civil rights coalition based entirely on race would not be sufficient to address the problem of white poverty.

A new generation of civil rights leaders now focuses its work on eliminating social and economic disparities, particularly for the indigent. Using some of the sixties strategies for community organizing around advocacy and service delivery, these leaders are bringing technical proficiency to such complex problems as economic development, improvement of schools, and the organization of community development corporations whose missions range from building housing to creating mini-industries.

The most effective of these leaders are people like Bob Moses, a key voting rights activist in the South in the sixties, who now teaches math literacy to prepare poor children for the technology-driven job market; Eugene Rivers, a founder of Boston’s 10-Point Coalition to disarm gangs and rehabilitate young lives; Hattie Dorsey, whose Atlanta Neighborhood Development Partnership helps rebuild decaying neighborhoods; and Robert Woodson, head of the National Neighborhood Enterprise Center, who brokered a truce among the District of Columbia’s most violent gangs and placed its members in paying jobs.

Most of the successful leaders in the post-civil rights movement operate in the nonprofit sector, primarily in community-based groups. They know how to reinvent themselves and their strategies by developing cross-cultural alliances and partnerships based on technical competence as much as on common goals; build public and private resource bases; and navigate the bureaucratic governmental maze for funding. And they are actively training a new generation of young leaders to succeed them. The skills they bring to the job include expertise in planning, finance, technology, and government. They know how to design programs that are appropriate for the complex, multi-layered issues inherent in their work and how to garner the resources to rebuild decaying infrastructures and overhaul human services to make them more efficient and less costly, even while pushing constituents to practice self-sufficiency.

In conclusion, two questions stand out. First, can diverse cultural communities (such as Puerto Ricans in New York City, Central Americans or Ethiopians in Washington, D.C., Asians and Latinos in Los Angeles) and nonprofit groups in civil society coalesce with elected officials and with one another to address the post-civil rights agenda? Second, as they face increased costs along with demands for both enhanced services and fiscal accountability, how can cities (including economically and institutionally recovering venues of reinvention like Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia) support all their citizens?